Here I want to talk about the different types of camera you can buy and why this matters when it comes to getting close to your subject. This is quite an involved article, so do give it some time and thought and please beware, the internet is awash with well meant but bogus information on this topic and it's taken me a long time to suss it all out for myself. I hope you find this helpful.

Before taking the leap to buying a DSLR or Mirrorless camera (we call these Interchangeable Lens Cameras, or ILCs for short), many people consider using Bridge Cameras, so let’s talk about them first. A Bridge camera is called a bridge camera because it bridges the gap between a compact digital camera (or mobile phone) and an ILC. Typically a bridge camera will have a large zoom (which I’ll talk about soon) but it will still be quite light. Bridge cameras are typically less expensive than ILCs and you can’t change the lens. Another thing to remember about a Bridge Camera is that it has a very small image sensor. Now, once again don’t worry if you don’t know what that means as I’ll explain that later. At this stage you just need to know that it’s the sensor size which is crucially important to how bridge cameras work. Bridge cameras are reasonably easy to use and are often all about their zoom range. You will hear people saying that “this camera has a 20 times zoom” or “50 times zoom”. I have a bridge camera which has an 83 times zoom but what does that actually mean? Well, once again, I will explain what it means later but for now all you need to know is that the bigger the zoom number, the closer the object you’re photographing will appear. Does it mean it will be 83 times closer? Well, sort of, but bear with me and all will become clear.

ILCs are what the serious hobbyists and professional photographers tend to use. They are expensive when compared with Bridge cameras and you have to buy lenses separately so that’s an additional expense. They are also much heavier than Bridge Cameras and when you add on the weight of bigger lenses with more zoom they just get heavier. However, the sensor inside an ILC is much bigger than inside a bridge camera. This means two things, firstly even with a huge lens a ILC will seem to struggle to get as close to your subject as a bridge camera, but the image quality you get will be much, much better.

When it comes to ILCs, Mirrorless cameras can be slightly smaller than DSLRs because, crucially, they do not contain the reflex mirror (hence the name) and they use different viewfinders. It is absolutely not the purpose of this article to explain the technical differences but mirrorless is newer technology and these cameras tend to be (but not always) smaller and lighter than DSLRs - that said, large lenses will always be heavy so the benefits of a scaled down Mirrorless camera may well be lost.

In ILCs there are also different sizes of sensor. Common sizes are "Medium Format", “Full Frame” and “Crop Sensor”. Cameras with Crop Sensors tend to be cheaper than Full Frame or Medium Format cameras and, as the name implies, have a slightly “cropped” or smaller sensor and this keeps the price down, consequently, these are the most popular ILCs for enthusiasts. Generally speaking, the larger the sensor the more expensive the camera. You cannot assume that the “bells and whistles” you get with your regular compact camera – like a swivelling touch screen for example will be present on the DSLR or Mirrorless you are interested in either but as time goes on and manufacturers have to compete with each other these features are slowly creeping into the DSLR market.

To be blunt: DSLRs and Mirrorless are for maximum image quality and Bridge Cameras are for convenience and economy.

Now let’s talk about zoom. Firstly let’s get Digital Zoom out of the way. All this means is that the software in the camera will enlarge part of the picture for you. It basically cuts out (or “crops”) part of the picture to give the impression of having zoomed in when all it’s really done is enlarge part of existing picture. Almost always this is results in very poor image quality (see the example in the last article here) and whilst it’s a handy feature for identifying a far off bird for example, it is usually best avoided for pictures you want to print.

Moving on to Optical Zoom. As I said above, Bridge Cameras tend to advertise themselves as having “86 times zoom” for example. In the world of ILCs they talk in terms of “focal length” which is measured in millimetres. Now these are just two different ways of describing the same thing but this is where things get a little bit complicated. I’ll try to explain it as simply as I can.

When the light shines into any digital camera it passes through the lenses which focus that light onto the sensor. Think of it like a projector: the lens is the projector and the sensor is like the screen. Let’s look at a very simple illustration:

To be blunt: DSLRs and Mirrorless are for maximum image quality and Bridge Cameras are for convenience and economy.

Now let’s talk about zoom. Firstly let’s get Digital Zoom out of the way. All this means is that the software in the camera will enlarge part of the picture for you. It basically cuts out (or “crops”) part of the picture to give the impression of having zoomed in when all it’s really done is enlarge part of existing picture. Almost always this is results in very poor image quality (see the example in the last article here) and whilst it’s a handy feature for identifying a far off bird for example, it is usually best avoided for pictures you want to print.

Moving on to Optical Zoom. As I said above, Bridge Cameras tend to advertise themselves as having “86 times zoom” for example. In the world of ILCs they talk in terms of “focal length” which is measured in millimetres. Now these are just two different ways of describing the same thing but this is where things get a little bit complicated. I’ll try to explain it as simply as I can.

When the light shines into any digital camera it passes through the lenses which focus that light onto the sensor. Think of it like a projector: the lens is the projector and the sensor is like the screen. Let’s look at a very simple illustration:

|

| Simplified illustration of light passing through camera lens |

This is what happens when we take a picture of a tree. The light from the tree (red, green and blue lines) passes through the lens and projects the image (back to front and upside down) onto the sensor or film inside the camera (the electronics in digital cameras make sure you always see the image the correct way).

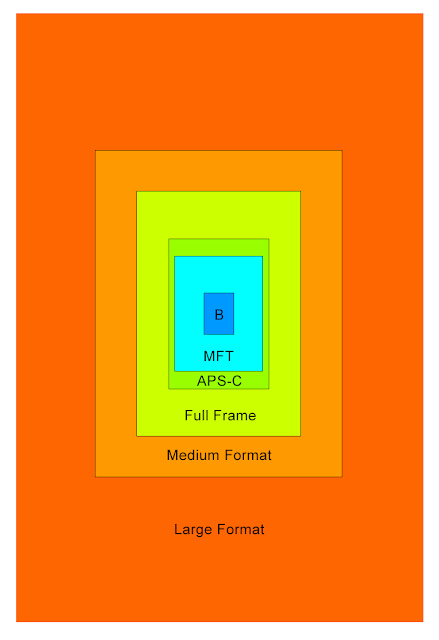

Now, in the picture above you can also see several rectangles all of which are representative of different film and sensor sizes found in different cameras and at their approximate scale. Let's take a much closer look at these relative sizes:

Large Format: Any film or sensor larger than 5 inches by 4 inches

Medium Format: Any film or sensor larger than Full Frame but smaller than Large Format.

Full Frame: The same size as 35mm film.

APS-C: Also known as a "crop" sensor

M4/3: Full name is Micro Four Thirds (MFT) and is four times smaller than Full Frame.

B: This is my abbreviation for the sensor found in bridge cameras and mobile phones

Thinking back to the picture of our tree, above. All things being equal, the large sensor can see the whole scene, whereas the smaller sensors can only see part of the scene. So even when everything else is identical, just having a smaller sensor in the camera gives the appearance of having zoomed into the tree - but as you can see, that's not what has happened, you are merely seeing a cropped version of the whole scene. So, depending on the camera you are using, and the size of sensor inside it, the image you can capture of exactly the same scene will vary. In technical jargon, this means that your Field of View (FoV), can vary depending on sensor size.

Now by moving the lens backwards or forwards I can make the image projected onto the sensor even bigger or much smaller. And that’s what optical zoom is. In technical jargon, that's the Angle of View (AoV). By Zooming in, I narrow the Angle of View and I see less of the whole scene, by zooming out I widen the Angle of View and see more of the whole scene. Different lenses will have a different Angle of View, and obviously the Angle of View of the lens will affect the Field of View of the camera: if a lens can see more, then so can the camera sensor. The following diagram illustrates the changing Angle of View with a zoom lens:

Large Format: Any film or sensor larger than 5 inches by 4 inches

Medium Format: Any film or sensor larger than Full Frame but smaller than Large Format.

Full Frame: The same size as 35mm film.

APS-C: Also known as a "crop" sensor

M4/3: Full name is Micro Four Thirds (MFT) and is four times smaller than Full Frame.

B: This is my abbreviation for the sensor found in bridge cameras and mobile phones

Thinking back to the picture of our tree, above. All things being equal, the large sensor can see the whole scene, whereas the smaller sensors can only see part of the scene. So even when everything else is identical, just having a smaller sensor in the camera gives the appearance of having zoomed into the tree - but as you can see, that's not what has happened, you are merely seeing a cropped version of the whole scene. So, depending on the camera you are using, and the size of sensor inside it, the image you can capture of exactly the same scene will vary. In technical jargon, this means that your Field of View (FoV), can vary depending on sensor size.

Now by moving the lens backwards or forwards I can make the image projected onto the sensor even bigger or much smaller. And that’s what optical zoom is. In technical jargon, that's the Angle of View (AoV). By Zooming in, I narrow the Angle of View and I see less of the whole scene, by zooming out I widen the Angle of View and see more of the whole scene. Different lenses will have a different Angle of View, and obviously the Angle of View of the lens will affect the Field of View of the camera: if a lens can see more, then so can the camera sensor. The following diagram illustrates the changing Angle of View with a zoom lens:

So, we can say that the Angle of View is determined solely by the lens you are using and this affects what your camera can see, but the Field of View is determined by both the lens you use (the Angle of View) and the sensor size in your camera.

In Compact cameras, Bridge cameras and Mobile Phones, magnification of the image is talked about in terms of "zoom factor". For example 3x zoom or 20x zoom or even 83x zoom. I posed the question above, does 83 times zoom on a bridge camera actually bring the image 83 times closer? Well that's what we're going to answer now.

Every lens has something called a Focal Length. Simply put, this is the distance, in millimetres, from the point in the lens where all the light from outside comes together (the convergence point) to the surface of the camera sensor where all the light is focused. In a lens with no zoom the focal length is fixed; it cannot move. However, in a lens that can zoom the focal length is variable; it can move. This means that the point of convergence will move back and forward inside of the lens, which has the effect of both lengthening or shortening the focal length and narrowing or widening the Angle of View. This simplified animation shows the process in principle:

A long focal length (say 600mm) gives a very narrow Angle of View (approx 3˚), and thus a lot of magnification. A very short focal length (say 10mm) gives a very wide Angle of View (approx 97˚) and thus very little magnification.

Important note. The focal length of a lens will always be the same: if a 50mm lens is on a crop sensor camera, then the focal length of that lens is still 50mm. If it's on a full frame camera, its focal length remains 50mm. All that changes is the Field of View: the crop sensor camera has a smaller sensor which equals a smaller Field of View. This introduces a concept called Full Frame Equivalency.

Full Frame cameras are basically the standard photographic format. If we deviate from that standard, by having a smaller sensor, it is helpful to create an equivalence so we can imagine how our images will be compared to the standard. To do this we need a "crop factor". The calculation for the crop factor is:

Full-Frame Sensor Diagonal (mm) ÷ Crop Sensor Diagonal (mm) = Crop Factor

For this explanation let's say this calculation comes to 1.6 for our crop sensor camera.

If I put a 50mm lens on my crop sensor camera, then the Full Frame Equivalency calculation is:

50mm x 1.6 = 80mm

16mm ÷ 1.6 = 10mm

And the "but" here is that it only magnifies 83 times from the shortest focal length available on that camera. So, if you zoom out all the way with your bridge camera, this will allow the camera to see as much as it can - it's largest Field of View. Now if you actually look at the picture you are going to take like this and then look at the same scene with your own eyes, everything is much bigger with your eyes. This is because the smallest focal length on bridge cameras is somewhere around a full frame equivalent of 24mm whereas the focal length of your eyes is about 50mm. The larger the focal length, the larger the image seems. So, what 83 times zoom means is that an image will appear 83 times larger than how it looks at an equivalent focal length of 24mm, not 83 times larger than how you see it. It's really just a big number to draw peoples attention and means very little. Using focal length and millimetres to describe zoom is actually pretty sensible, as it's connected to a standard which is easily understood.

What’s the point in telling you all of this? Well, the point is to know roughly what a focal length is, how it relates to magnification (or optical zoom), how that’s affected by the particular lens and sensor size in the camera and how that will affect your photography. If you want to get close to a subject that is far away (or very small) you are going to need to have a large focal length. Even though bridge cameras are advertised as having say “83 times zoom” that same camera will also have the equivalent focal length information buried somewhere. In the case of that particular bridge camera, the lens only has a real focal length of 357mm but, because the sensor is so small, that gives it a Full Frame Equivalency of 2000mm. So, to get an image to appear as close with a full frame DSLR camera you would have to buy a 2000mm telephoto lens which would be, frankly, unfeasible for most people due to the breathtaking price, outlandish size and staggering weight of such a lens.

Given that, why would anyone buy a DSLR or Mirrorless camera? A couple of reasons. Those small sensors in bridge cameras (Marked "B" in the picture above) make distant things seem really close, but at the expense of image quality which can seem very artificial when looking closely (called "pixel peeping"). Because the lenses are of a small size, they don’t let in as much light as large telephoto lenses and less light means poorer image quality. These lenses are also relatively inexpensive and cheaper lenses usually means you will start to see chromatic aberration - don’t worry about that just now though, I have a separate article dedicated to Chromatic Aberration. More expensive ILCs also come with other features that cheaper cameras don’t, like the ability to take 20 pictures per second for example – when a bird is jumping around quickly, think how useful that would be to capture the perfect moment. The picture quality in DSLRs and Mirrorless is consequently much better and can also allow you to crop the final image to give a better final result.

Now, of course, everything I mentioned above about image quality is relative and depends very much on what you are going to be doing with your image. If you are printing large posters or selling to magazines then image quality is vitally important. If you are sharing amongst friends on social media and for your own use then image quality doesn’t matter quite so much – noisy images and pixelation (which I will speak about in another article) don’t matter all that much when you are looking at small versions of your image, either on the internet or printed out at standard sizes. Many people like to carry a bridge camera instead of carrying binoculars – they can carry a light and reasonably inexpensive camera to record what they see and or to identify something later if it’s very far away. As I said above, both are very good at what they do, and both have their place if you understand the limitations.